According to Paul Johnson (shown above in 1970) it’s a ‘relativistic world’ and we just live in it.

Marx, Freud and Einstein all conveyed the same message to the 1920s:

the world is not what it seems.– Paul Johnson, ‘Modern Times’ (1985)

I had never heard of Paul Johnson until his recent passing was noted at the end of an episode of the politically conservative Commentary podcast. I rarely listen to these podcasts in their entirety, but I made it to the end of the January 13 episode because I had nothing better to listen to one sunny Sunday afternoon while raking the last of the autumn detritus in my yard.

After hoisting Joe Biden ‘on his own petard‘ over the latest classified documents scandal, host John Podhoretz closes out the podcast by “paying tribute to Paul Johnson, who died yesterday at the age of 94,” then describing Johnson as a ‘self taught amateur popular historian’ who…

…wrote what was arguably one of the most important books of the last half of the 20th century. That was Modern Times, published in 1985, in which he locates the beginning of the New Age to the experiment in South America in 1919 that provided scientific proof of the Theory of Relativity.

Oh? That got my attention.

Though I’d never heard of Johnson, I was familiar with the event Podhoretz was referring to: The Eddington Expedition – which I first heard of in the mid-1970s when Pem Farnsworth told me how that event had influenced her late husband when he was still a boy living on a farm in Idaho.

As I wrote in the first chapter of The Boy Who Invented Television:

Einstein encountered tremendous resistance to his radical theories among the scientific establishment, but there was no such difficulty for an aspiring young scientist in the hills of Idaho whose imagination was not saddled with any preconceived notions of the workings of the physical universe.

During a visit to a neighboring ranch (Philo) happened upon a newspaper article about an international expedition that had sailed to Africa in May, 1919 to test Einstein’s theories by observing a solar eclipse. Led by the British astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington, the expedition arrived in Africa at a time when Europe was still reeling from the devastation of the Great War, yet scientists from both Allied and Axis nations had teamed up for the mission.

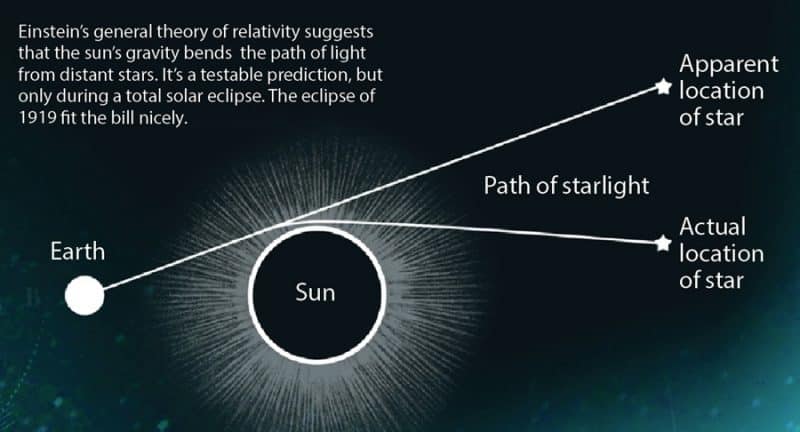

Eddington reasoned that if space could be stretched, as Einstein suggested, then light could also be stretched by the presence of a large gravitational mass like the Sun.

When the eclipse had darkened the West African sky, Eddington’s team photographed starfields around the Sun that were not visible during normal daylight. When these photos were compared with photos of the same starfields taken when the Sun was not present, Eddington found a difference in the apparent location of the stars—just as Einstein had predicted.

The Eddington Expedition was recorded as a defining moment in 20th century science.

Just as John Podhoretz had quoted Paul Johnson.

It’s great when a ‘higher authority’ agrees with me.

So I tracked down a copy of Modern Times and, sure enough: The first chapter is entitled ‘A Relativisitic World.’ It begins with:

The modern world began on 29 May 1919 when photographs of a solar eclipse, taken on the island of Principe off West Africa and at Sobral in Brazil, confirmed the truth of a new theory of the universe….

The rest of Johnson’s first parapraph condenses the historic shift from “Newtonian comsology, based upon straight lines of Euclidean geometry and Galileo’s notions of absolute time, until…

In 1905, a 26-year-old German Jew, Albert Einstein, then working in the Swiss patent office in Berne, published a paper ‘On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,’ which became known as the Special Theory of Relativity.

Einstein’s theory, and [Cambridge Professor Arthur] Eddington’s much publicized expedition to test it, aroused enormous interest throughout the world in 1919. No exercise in scientific verification, before or since, has ever attracted so many headlines or become a topic of universal conversation.”

And this, Paul Johnson asserts, is the beginning of our modern, ‘relativistic’ world.

Television: The ‘Relativistic’ Household Appliance

For years, I have been trying to make the case that television is a manifestation of that ‘relativistic’ world in a common household appliance. The connection may be indirect, but let me see if I can make it.

When most people think of Einstein think of ‘relativity’ and its most famous equation, E=mc2.

What few people know is that Einstein won his Nobel Prize in 1921 not for the Theory of Relativity, but for his work on the photoelectric effect.

A basic knowledge of The photoelectric effect had been around since the 1880s, when Heinrich Hertz – for whom electromagnetic frequencies are named – observerd that electrons are emitted when ultraviolet light shines on certain metal surfaces.

The Came Annus Miraculous – 1905

The relativistic world took shape when, twenty years later, Einstein defined and quantified what Hertz discovered in a treatise with the cumbersome title On a Heuristic Point of View Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light. In the years that followed other scientists began to develop photoelectric cells, which were used in the earliest attempts to transmit moving images by wire-or-wireless by spinning perforated discs in front of a photocell.

Purely electronic video arrived on the planet a year after Einstein was awarded his Nobel Prize – when a kid plowing a field in Idaho got the idea that he could replace all the spinning discs and mirrors with a magnetically deflected field of electrons. He got the idea in his head in 1922, and demonstrated it on a workbench in 1927.

The arrival of electronic television was the first time that the Einstein’s theories were put into practical use – in what has since become the most ubiquitous device on the planet: the video display (i.e. the thing you are looking at right now!). In the decades since, that relativistic reality has migrated from our living rooms to our pockets.

Einstein’s Cosmological Cortex

What ‘relativity’ and ‘television’ have in common is that their theoretical foundations both found substance in the cerebral cortex of the same individual, Albert Einstein.

My point is that both relativity and the photoelectric effect – which led directly to Farnsworth’s invention of electronic video – came from the same cosmology, the same evolving understanding of how the universe works. The Photoelectric Effect and Relativity are different sides of the same coin, which for the sake of convenience we’ll call part of ‘Our Relativistic World’ – which is exactly what Paul Johnson called it in the first chapter of Modern Times.

Relativity – What’s It Good For?

While the Theories of Relativity may define the universe, we get much more practical use out of the Photoelectric Effect on a daily basis.

The only practical appliation of E=mc2 comes in the form of nuclear fission reactors, from which we get some of our electricty; Fortunately the other primary use – bombs – has not been used for anything other than testing since 1945.

But the photoelectric effect? Oh, my. Countless technologies rely on Einstein’s explanation of the photo electric effect:

- photocells and photodiodes are used in everything from street lights to burglar alarms;

- CCD and CMOS sensors in our cameras and smartphones;

- lasers that are used in all manner of industry and communications (remember CD players?);

- the fiber optics that make the Internet possible.

The list goes on and on, but electronic video was among the first and is still the most familar use of the cosmology that produced both Relativity and the quantification of the Photoelectric Effect.

Thank you, Albert.

What does any of this have to do with Townsend Brown?

Well, there’s that part in General Relativity about the bending of spacetime. While it may seem like a long time from 1905 (or 1922/27) to 2023, ‘Our Relativistic World’ is barely out of its infancy.

All of this coincides with my own journey, following the parallel paths of Farnsworth and Brown. Both were born within year of Einstein’s Annus Mirabulous (1905) and both received their seminal inspirations in their teen years in the early 1920s – about the time Einstein was awarded his Nobel.

The Townsend Brown component of the narrative is about that ‘bending of spacetime’ – through the electrical induction of synthetic gravitational fields. That idea holds the promise – as Brown expressed it to his future wife in 1928 – that someday “mankind will just push away from the Earth as easily…” as their sailboat pushed away from the dock.

I agree with Paul Johnson that the Eddington expedition marks the beginning of our ‘Modern Times.’

I also believe that on that occasion, mankind crossed a threshold into a new realm of knowledge and practical application – the surface of which has barely been scratched.

The question remains: if gravity control is the next step, then why hasn’t it been taken?

Returning to Johnson: The world is not what it seems, and that is still true, and, near as I can tell, even more so in the story of T. Townsend Brown.

But given how litttle we know, that’s all we know.